What is carb cycling?

In the most basic format, carb cycling is a planned alteration of carbohydrate intake in order to prevent a fat loss plateau and maintain metabolism along with workout performance.

Carb cycling is considered an aggressive and high level nutrition strategy. Only people (such as physique athletes) whose nutritional adherence is extremely high, and who require a more meticulous nutritional approach, should use it. Carb cycling is designed for short-term use. It is not a long-term solution for body fat management. In fact, if used for too long it may be downright unfavourable.

Why would carb cycling be important?

Short term vs long term restriction

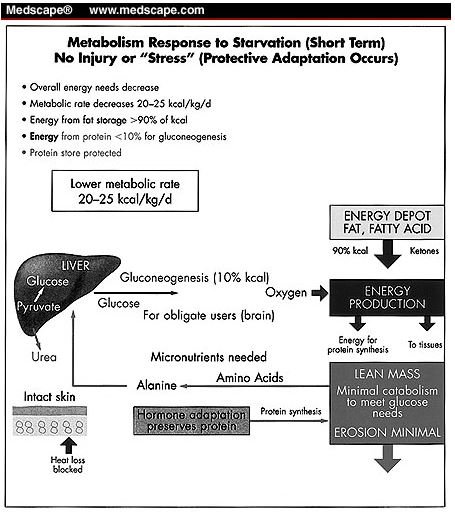

It’s important to distinguish between the immediate (short term) and chronic (long term) effects of carbohydrate and calorie restriction. Although the body handles short-term deprivation relatively well, a strict nutritional regimen of low calories or low carbohydrates can be hard on the body over the long haul. Missing a meal here or there, or dropping carbohydrates very low, isn’t disastrous when it’s occasional and brief.

Some evidence even suggests that brief and relatively infrequent periods of fasting and/or carbohydrate restriction may actually be advantageous for both health and body composition. For example, a recent study in the American Journal of Cardiology (Horne et al 2008) noted that occasional and short bouts of fasting (e.g. 24 hours) improved markers of cardiovascular disease.

However, restricting calories and/or carbohydrates for longer periods (as in the case of physique athletes, who may diet for months before a competition) can have negative metabolic effects. Because endocrine systems are interconnected (for instance, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal [HPA] axis, which is the body’s Mission Control for hormones), these effects can be wide-reaching.

For example, as a result of long-term restriction, dieters may experience reduced metabolic rate, thyroid hormone output, sympathetic nervous system activity, spontaneous physical activity, leptin levels, and reproductive hormone output (Douyon 2002; Friedl 2000; de Rosa 1983; Klein 2000; Ahima 2000; Weyer 2001; Mansell 1988; Kozusko 2001; Dulloo 1998).

Not only can this have consequences for overall health, it can bring body composition gains to a standstill.

Metabolic response to short-term starvation

Metabolic response to short-term starvation

So, if you can’t just “out-diet” your body’s control center, what are you to do? This is where carb cycling comes in.

Planned manipulation and variation

If eaters plan a higher carbohydrate intake at regular intervals, their bodies won’t ever get too close to starvation mode. However, they can still lose fat if they still take in fewer total calories than they expend — i.e., if the overall long term trend is towards negative energy balance. Higher carbohydrate intake days can increase thyroid output and control hunger (Douyon 2002; Friedl 2000; de Rosa 1983).

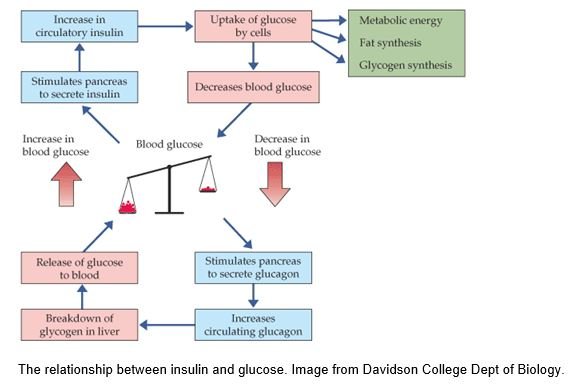

Manipulating carbohydrate intake can also help one take advantage of certain anabolic hormones, namely insulin. Insulin regulates amino acid and glucose intake entry into the muscle cells. If insulin is seldom elevated, dieters will not reap its anabolic benefits. Conversely, if people plan to elevate insulin levels at the appropriate time with a scheduled higher carbohydrate intake, they can maximize insulin’s potential anabolic effects.

There are different methods of carb cycling. However, the common theme behind them is that protein and fat intake stay relatively constant while carbohydrate intake is manipulated. Carb cycling also typically involves calorie cycling. Since carbohydrates have 4 calories per gram, adjusting carbohydrate intake while keeping fat and protein more or less the same can greatly alter calorie intake.

Days where carbohydrates (and usually calories) are increased are often known as “re-feed” days. Dr. Berardi gives a nice definition of re-feed as a planned increase in calorie intake that lasts 8 – 12 hours and usually consists of a large increase in carbohydrates. Re-feeds usually occur when dieting and are scheduled in order to provide a brief day of psychological relief as well as a number of physiological benefits. An example of a re-feed is following a strict diet of 1500kcal 5 days per week and consuming 2500kcal of clean bodybuilding foods (the additional kcal coming mostly from carbohydrates) on the other 2 days.

Since carbohydrate intake will be increased on the re-feed days, it is important to scale back the fat and protein intake slightly. Carbohydrates have a protein sparing effect so less dietary protein is required. This will allow for one’s calorie count to remain in check.

The same principles of good nutrition apply equally to “everyday” eating and carb cycling phases, including proper meal frequency, omega-3 fat intake, adequate protein and fiber intake, plenty of vegetables, etc.

Here are some common carb cycling approaches.

Infrequent, big re-feeds

Higher carbohydrate intake every 1-2 weeks during a lower carbohydrate intake phase.

Frequent, moderate re-feeds

Higher carbohydrate intake every 3-4 days during a lower carbohydrate intake phase.

Strategic carb cycling

This consists of structuring different menus with moderate carbohydrate intake at strategic intervals during a lower carb intake phase. This approach steers away from an extremely high carbohydrate intake because the menu changes regularly. But it does allow for metabolism to play catch-up with dietary intake.

Carb cycling for muscle gain

Those interested in gaining muscle mass need a calorie surplus. Unfortunately, if they grossly over-consume calories for too long they’ll probably gain bodyfat. Thus, one way to optimize muscle gain over fat gain during a muscle gaining phase is with carb cycling. This is similar to the “strategic carb cycling” approach. Menus are planned according to your weekly schedule in order to create a temporary calorie surplus. This can assist with lean mass and strength gains.

Sample menu

Here’s how a sample week of carb cycling might look.

| Day 1 Lower carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains only after workout No workout drink today No fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

Day 2 Lower carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains only after workout No workout drink today No fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

Day 3 Moderate carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains during breakfast and after workout No workout drink today 1 piece fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

| Day 4 Lower carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains only after workout No workout drink today No fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

Day 5 Lower carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains only after workout No workout drink today No fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

Day 6 Higher carb daySmall portion of starchy veggies and/or whole grains with every meal Have a workout drink today Can have 2-3 pieces of fruit today Fill the rest of your day with lean proteins, green/fibrous veggies, and healthy fats |

| Day 7 Back to Day 1 |

||

Important tips for each carb cycling approach

- Base the dietary approach on basal calorie needs and activity levels.

- Always pick out the re-feed days in advance.

- Stay on course until the re-feed day arrives.

- Keep your decisions outcome-based. Different re-feed strategies work better for certain body types. Look at the evidence from your photographs and body composition tests to ensure that you are on the right track.

- Try to exercise on the re-feed days for optimal body composition results.

- On the re-feed days, the body still tolerates carbohydrates best first thing in the morning and around times when physical activity is high.

For extra credit

Carb cycling may help control leptin and ghrelin levels. These are appetite and fat homeostatic hormones — in other words, they are sensitive to body composition and food intake; their job is to try to make sure we eat enough and have enough body fat.

Carb cycling can maximize glycogen stores and improve workouts during a low calorie period.

With a lower carbohydrate intake, fiber intake will also be lower. Make sure to consume high-fiber foods and supplements and drink plenty of water to prevent constipation.

Metabolic “up-regulation” doesn’t always scale directly with intake and too much re-feeding can result in body fat gains (Dulloo, Samec 2001). So don’t use carb cycling as an excuse to pig out.

Summary and recommendations

- Use carb cycling only if you are nutritionally advanced and have exhausted basic methods.

- Use only for a short duration.

- Pick a carb cycling strategy depending on how you feel with lower carb intake days, how much muscle mass you carry, your physique goals and length of time you anticipate on the carb cycle.

- After a carb cycling strategy has been selected, you need to establish your calorie intake goal.

- Second, establish a protein intake goal (which remains relatively constant).

- Third, establish a fat intake goal (again, relatively constant).

- Finally, pick a carbohydrate intake goal for the different days. Then divide your total intake of all the nutrients up into regular feeding intervals with appropriate spacing due to workouts.

- Schedule the re-feeding times. You are ready to go!

Here’s additional reading on this topic:

Get Shredded (PDF)

Getting Unshredded (PDF) (Transitioning off the GS plan)

References

Horne BD, et al. Usefulness of routine periodic fasting to lower risk of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography.Am J Cardiol. 2008 Oct 1;102(7):814-819. Epub 2008 Jul 10.

Dulloo AG, Samec S. Uncoupling proteins: their roles in adaptive thermogenesis and substrate metabolism reconsidered. Br J Nutr 2001;86:123-139.

Douyon L, Schteingart DE. Effect of obesity and starvation on thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and cortisol secretion. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002;31:173-189.

Friedl KE, et al. Endocrine markers of semistarvation in healthy lean men in a multistressor environment. J Appl Physiol 2000;88:1820-1830.

de Rosa G, et al. Thyroid function in altered nutritional state. Exp Clin Endocrinol 1983;82:173-177.

Klein S, et al. Leptin production during early starvation in lean and obese women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2000;278:E280-E284.

Ahima RS, et al. Leptin regulation of neuroendocrine systems. Front Neuroendocrinolgy 2000;21:263-307.

Weyer C, et al. Changes in energy metabolism in response to 48 h of overfeeding and fasting in Caucasians and Pima Indians. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:593-600.

Mansell PI, MacDonald IA. The effect of underfeeding on the physiological response to food ingestion in normal weight women. Br J Nutr 1988;60:39-48.

Kozusko FP. Body weight setpoint, metabolic adaption and human starvation. Bull Math Biol 2001;63:393-403.

Dulloo AG, Jacquet J. Adaptive reduction in basal metabolic rate in response to food deprivation in humans: a role for feedback signals from fat stores. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:599-606.